What Comes After Virtue?

After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory is Alasdair MacIntyre’s bombastic approach to resuscitating virtue ethics, which is the system of ethical thought devised by Aristotle. While virtue ethics has a lot to offer, MacIntyre believes all ethical discourse since the end of the Medieval Era has been totally in error. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and MacIntyre fails to provide it.

Among his chief concerns is that contemporary ethical models are derivative of emotivism in that they have no solid basis and are relativistic. They cannot tell people what they should or should not be doing since all such judgments are just a matter of perspective without rational grounding. To explain why the world is this way, he goes through a prolonged history of philosophy, concluding that the Enlightenment was a moral failure because it did not produce a central, rational foundation for ethical discourse. In this view, Utilitarianism and Deontology are both fatally flawed, leading only to the relativist, fractured state of ethics today.

MacIntyre does provide reasonable critiques about over-specialization, the problems of divorcing philosophy from history, consumerism, needless bureaucracy, and social sciences masquerading as hard sciences when they cannot produce anything near the reliability of the hard sciences. On his central point, however, he is inadequate, even for someone who is sympathetic toward virtue ethics.

The Needs of the Many

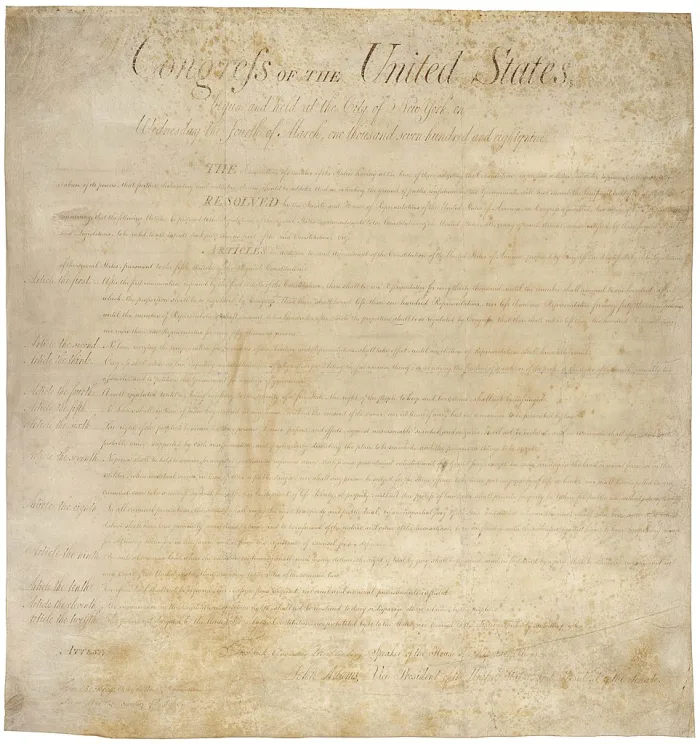

For MacIntyre, Utilitarianism is wrong because it cannot offer evidence for what someone should choose among competing ideas of “good” because it cannot define happiness. As such, it cannot fulfill its directed aim of maximizing happiness and good for as many people as possible. Likewise, Deontology, particularly as founded by Kant, cannot create rational moral imperatives that make sense universally, as Deontology strives to do. MacIntyre concludes that the Enlightenment that produced these philosophies was a moral failure. MacIntyre claims, “Natural or human rights then are fiction” (70). This conclusion might come as a surprise to anyone living in Western Liberal Democracies, which are rooted in no small part in Utilitarianism and the not unreasonable belief in human rights.

Rights, Human and Otherwise

One issue MacIntyre takes with the idea of “rights” is that they are an invention of the late Medieval and early Modern eras. Also, because language has changed over time, not only did the Classical Greeks have no equivalent word for “rights,” they clearly have not existed as through human civilization. The latter linguistic argument does not hold water. Classical Greek also did not have a word for “tsunami,” obviously, but that does not mean they did not happen. Historical records of ancient Greece and all of the Mediterranean show tsunamis happen. Likewise, in Classical Athens, the hierarchical divisions, privileges and expectations of citizens are all evidence that a concept of “rights” existed in action if not in language. One can say that Classical Athenians didn’t believe in “human rights,” but that’s hardly proof that “rights” as a social notion did not exist. To give a similar example, until the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese language did not have a word for “fine art.” This did not mean that Japanese culture lacked artistic understanding or aesthetics. Just because a word does not exist does not mean the conditions of reality precluded anything.

What MacIntyre lacks is a sufficiently robust understanding of cause and effect.

Pragmatism

To take a different critical approach to MacIntyre’s claims, so what if “rights” are an invention? He doesn’t go to any lengths to explain why their creation is in any way wrong. In fact, I’d suggest a great many people alive today are happy for and at least attempt to avail themselves of their rights as citizens and human beings. What MacIntyre lacks is a sufficiently robust understanding of cause and effect. Even if “rights” did not exist in the past, they exist now.

Part of MacIntyre’s problem here comes from his total non-engagement with Pragmatism, which seems to be a much broader problem in that he doesn’t bother with America much at all. Pragmatism is dispensed with in half a sentence and never brought up again, despite being a philosophy opposed to emotivism (66). However, Pragmatism, with its general lack of metaphysics and assent to life’s mutability, completely accepts that something is real because it creates changes in the world and people’s behavior. Therefore, a Pragmatic approach has no issue with the alleged creation of “rights” because if they weren’t real before, they are now that people have made them and live by them. MacIntyre, however, would rather avoid or pretend not to notice a philosophical tradition that undercuts one of his core concerns.

Teleology

MacIntyre stresses that virtue ethics is teleological, while other ethical philosophies are not. While this may be true, it doesn’t explain why it is superior to others or more worthwhile. He also points out that virtue ethics is rooted in a tradition that includes Classical Greece and late Medieval Catholicism through Saint Thomas Aquinas. He admits these traditions included elements that are and have been reprehensible for some time—like misogyny or slavery—but provides no explanation as to what should be done about it, even within his own philosophical framework. He argues tradition helps provide context and a goal for human action in judging what is good, but he doesn’t really get into the real notion that what is “good,” even within a single tradition, changes over time. The letdown in this is that the flexibility of virtue ethics is one of its best features. Nietzsche also makes the point that virtues and vices change over time, but for as often as MacIntyre brings him up, he never bothers to mention that.

Clarity

MacIntyre mentions several times how clear he’s being. Just because someone keeps saying they’re being clear doesn’t mean they are. He does not make an obvious statement as to why virtue ethics is better than other ethical philosophies. He gestures toward some of his own writing. His lack of clarity to any non-specialized reader is obvious in his own definition of a virtue as being “an acquired human quality the possession of which tends to enable us to achieve those goods which are internal to practices and the lack of which effectively prevents us from achieving any such goods” (191). This definition is hardly different in character from the many non-statements given at corporate press briefings that border on Orwellian Doublespeak. Even in context, it is awkward. Maybe it would have been helpful if MacItyre had started his book by defining his terms rather than with the apocalyptic language of how everyone lives in the wreckage of failed ethical discourse. The result is that MacIntyre, while claiming clarity, is less coherent in his ethical standpoint than Crime and Punishment, or The Lord of the Rings, or Disco Elysium.

Eudaimonia

There is plenty of other trouble across After Ethics: MacIntyre’s ambivalence toward facts, lamenting the separation of law and morality, a sentimentality toward revenge killing, that Benjamin Franklin is the only American he bothers to talk about at length, and his pretending that tradition and narrative have no role in contemporary culture, among others (79, 152, 166, 182-7, 220-7). Unfortunately, it doesn’t do a compelling job of defending virtue ethics.

Source

MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue. Notre Dame Press, 2007.

© 2023 Seth Tomko