What allows these movies to transcend being simple horror genre films is the evolving, layered symbolism of the titular undead.

Night of the Living Dead

In this 1968 movie the reanimated corpses of the recently deceased attack survivors barricaded in a Pennsylvania farmhouse. Catching bits of news from television and radio, they hear theories of a radioactive satellite returning from a mission to Venus. Nothing conclusive is stated, and since none of the theories help the survivors the information means little to them. They must instead focus on short term survival in a surreal and ghoulish situation.

These explanations in the official reports, however, did affect the audience by tapping into Cold War fears concerning space travel and radiation from nuclear testing. In a similar fashion the mindless, all-devouring living dead are a manifestation of anxiety concerning desperate hungry and faceless mobs in America and abroad following the population explosion after World War Two.

Dawn of the Dead

In Romero’s second film zombies take on more nuanced symbolism. Early in the film police and military forces attempt to contain both zombie outbreaks and mobs of panicked, impoverished minorities. Little discrimination is shown in trying to deal with with group; a minor character even suggests the same lethal action be taken against the living and the dead as he spouts racist rhetoric before military action. Right away, the audience develops a sense of empathy for anyone, including zombies, who are on the receiving end of militarized aggression that in no way provides a solution to the mounting troubles.

When the survivors are establishing a base in a nearby mall they question why so many zombies are drawn to the place. They theorize that the mall had an influence on them in life, so the zombies would be drawn their by their remaining primitive instincts. The audience can see the zombies as a comment on consumerism. The living dead are, in fact, the ultimate consumers since they literally do nothing but tear down and consume everything they find. All at once, the zombies stand in as both victims of violence, perpetrators of violence, unthinking, ravenous consumers and as victims of both their own insatiable, reflexive desires, and symbols of inevitable decay and death.

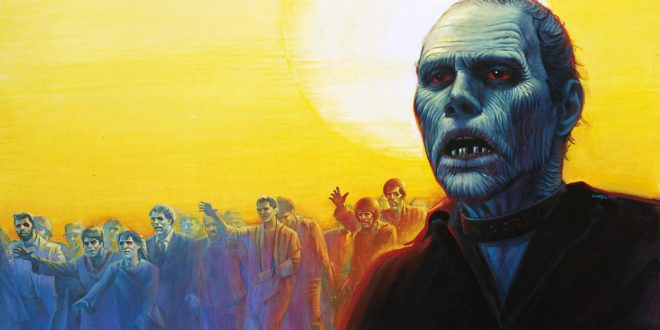

Day of the Dead

Film number three casts the zombies as a natural force. The military personal sees the zombies as sport kills or a security problem. In either instance there is nothing human about the living dead; they are simply another problem to be eliminated. The only real difference is that the military finds some glee shooting zombies rather than filling sandbags or transporting clean water. The scientific researchers, similarly, treat zombies not as former humans but as subjects to be mercilessly probed, tested, and dissected. While their goals and methods are different, the researchers place no more value on the zombies than the military does.

Day of the Dead uses the zombies as a barometer of the inhumanity of the surviving humans. It is the latter who has the capacity to be virtuous, but they instead spend their time tormenting the living dead and fighting one another over even the most petty of points. It is the zombie Bub who displays the most positive character traits while the living taunt and betray each other into annihilation. The hostility and general lack of empathy portrayed by the humans leaves the zombies as the object of audience sympathy in part because they cannot deny their nature, but better behavior should be expected from the living.

The Dead Shall Walk the Earth

In each instance the zombies are more than a typical horror movie villain. In fact they frequently come across as pitiable automatons when compared to the willful violence and destruction of the surviving humans. In each film the audience is invited to see another aspect of the zombies and what they mean not only to the characters in the movie but also to the viewers and the world around them.

© 2010 Seth Tomko