The Grand Inquisitor’s Theory

In The Brothers Karamozov Fyodor Dostoyevsky brings the theme of responsibility to bear on all of his psychologically tormented characters. At every turn one character or another seeks to escape from beneath the terrible weight of being held accountable for his or her choices.

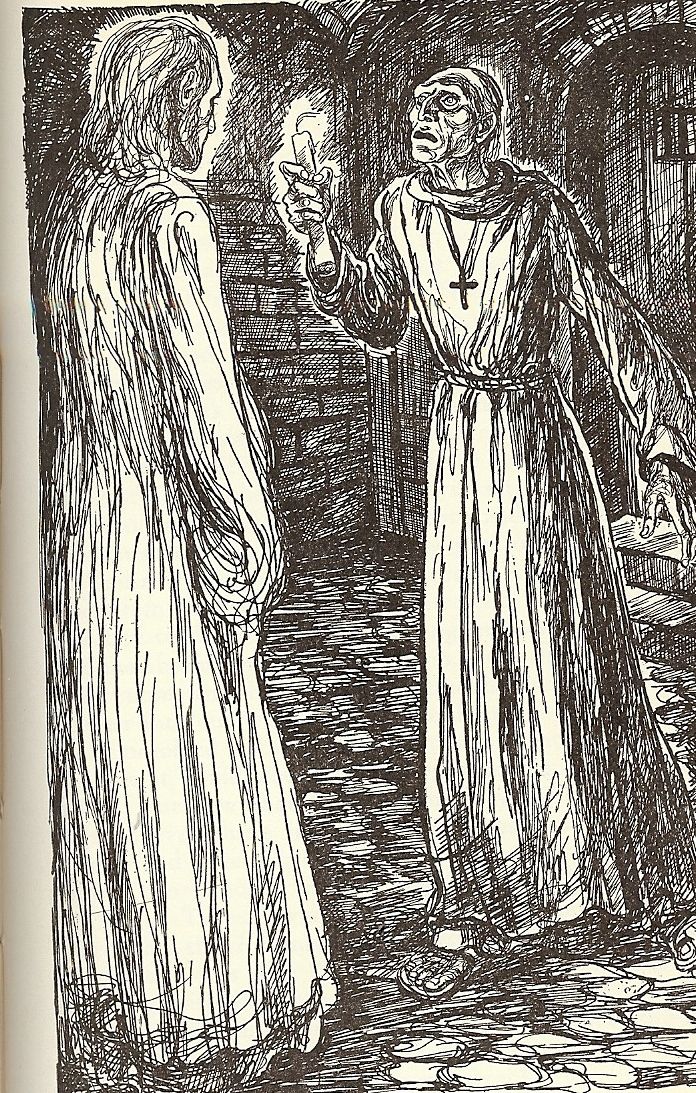

This escapist philosophy is spelled out by Ivan in his story of the Grand Inquisitor. While holding the returned Christ captive, the Grand Inquisitor berates Him and His terrifying mercy and proclaims mankind does not want the freedom Jesus offers from the Cross. The Inquisitor says, “Nothing has ever been more insupportable for a man and human society then freedom” (223). There is simply too much responsibility that comes with being free.

To rid themselves of this freedom humans place their fates in the hands of others. Dostoyevsky writes, “So long as man remains free he strives for nothing so incessantly and so painfully as to find someone to worship” (234). People can acclimate to and may come to enjoy their slavery; life is easier if one is free from having to make decisions and take responsibility for his or her actions. The Grand Inquisitor sees all humanity crying out “save us from ourselves” and is willing to oblige (238). He sees himself as performing a service to mankind and justifies his actions by saying, “Men rejoiced that they were again led like sheep, and that the terrible gift that had brought them such suffering, was, at last, lifted from their hearts” (237). People shrink from the burden of self-directed freedom; if they accept it they must own up to their own deeds.

Alyosha as Savior

It is disturbingly ironic that Alyosha, the holiest and humblest character, becomes a counterpart to the perverse religious message of the Grand Inquisitor. With alarming frequency, other characters heap their troubles and their decisions upon Alyosha, and they expect him to step in like the Grand Inquisitor and shoulder this awful burden for them. When Katerina is considering her situation with Dmitri she calls for Alyosha’s help:

“I feel instinctively that you, Alyosha,” she said taking his cold hand in hers, “I feel your decision, your approval, will bring me peace, in spite of all my sufferings. After your words, I shall be calm and submit—I feel that.” (177)

Such a scene is exactly what the Grand Inquisitor spoke about. Katerina is unwilling to take any action without the validation of someone she regards as a higher authority, in this case, Alyosha and the holiness he carries with him. She requires his approval and his strength to carry out her own plans even though Alyosha professes he knows nothing about such matters of the heart.

Gruchenka later makes the same demand of Alyosha. Plagued by her inability or unwillingness to decide whether or not to go see her former lover, she shuns all responsibility by thrusting it upon Alyosha:

Tell me, do I love that man or not? The man who wronged me, do I love him or not? Before you came, I lay here in the dark, asking my heart whether or not I loved him. Decide for me, Alyosha. The time has come, it shall be as you say. Am I to forgive him or not? (327)

The consequences of her action are too much for her to carry. Grushenka demands someone else take control of her life, someone who can relieve her of the pain in her life. Whether or not Alyosha makes the correct decision is almost inconsequential. As long as he makes the decision for her, Grushenka is no longer accountable for the results of her actions.

Other Karamazovs

Dmitri and Ivan are hardly any better. Dmitri explains away his behavior saying, “I’m a Karamazov. For when I do leap into the pit, I go headlong with my heels up, and I am pleased to be falling and pride myself on it” (105). His rationalization that sinning is simply in his blood is just another means of escaping accountability. Ivan is not a particularly admirable character either. His repetition of Cain’s question, “Am I my brother Dimitri’s keeper” should be enough to call his ethicality into question (214). Nor does Ivan want to accept even his tangential responsibility for the death of his father. Smerdyakov singles Ivan out as the inspiration for his crimes:

You are still responsible for it all, since you suspected murder and wanted me to do it, and went away knowing all about it. And so I want to prove that you are the only real murderer and that I am not the murderer, though I did kill him. (568)

Even with all his great intellect, Ivan cannot extricate himself from Smerdyakov’s logic; he is the true prime-mover behind Fyodor’s murder. While this argument might be questionable in a legal context, Ivan, ever the philosopher, has trouble denying a core of truth in it. In the end Dmitri and Ivan manage to take responsibility for their behavior though at a terrible price. Ivan is consigned to madness maybe even death, and Dmitri must atone for his “Karamazov” behavior through frostbitten labor in the frozen hell of the Tunguska Plains in Siberia. Dmitri, though, may seem a bit more noble as he accepts this punishment and the redemption it will bring rather than trying to escape and ignore responsibility for his actions again.

Dostoyevsky’s Dilemma

A lengthy and visionary work The Brothers Karamozov gropes for meaning in a world poverty-stricken of personal responsibility. The Grand Inquisitor believes few people are strong enough to accept Christ’s offer of true freedom especially with the dire suffering and responsibility that accompanies that freedom. Given the events in Dostoyevsky’s novel there appears to be little evidence to contradict the Grand Inquisitor.

Source

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamozov. Trans. Constance Garnett. New York: Signet Classics, 1957.

© 2010 Seth Tomko