Taking the Challenge

Initially laid out by Gary Gygax—creator of Dungeons & Dragons—in 1975, the essay was an early attempt at giving actionable advice to everyone looking to create and start their own setting to have tabletop fantasy roleplaying adventures. Ray Otus later streamlined the advice from Gygax into a pragmatic and straightforward agenda that anyone can follow by being creative and marking some boxes as a means of tracking one’s progress.

The benefit of this challenge is that it puts creators on a schedule and makes them accountable to themselves to get through the process, which can otherwise appear intimidating or allow someone to get sidetracked or bogged-down by following too many details. Obviously originally designed with D&D in mind, the edits and worklist made by Otus makes “The Gygax 75 Challenge” system agnostic. A potential creator could use it to develop a setting and campaign opening for D&D, Call of Cthulhu, Shadowrun, Deathbringer, Kult: Divinity Lost, Runequest, Shadowdark, or any number of different TTRPGs.

Week One

This is the concept stage. Creators should take the time to gather ideas for what kind of game they’re going to run and write up several bullet points meant to emphasize the atmosphere and expectations of the game. Will it be high fantasy with lots of magic? Will the adventures be primarily urban? Is injury and death to be a constant threat and expectation? How mature is the tone? Knowing these details helps the creator know the scope of the kinds of adventures they’re going to run and lets players know too and buy in. It should also help everyone get on the same page. A game of swashbuckling adventure on the high seas with limited magic but rudimentary firearms lets players know this won’t be the right occasion to play a character who wears plate mail and brings divine retribution to all heretics. This is also the time for creators to list about a half dozen sources—for themselves and/or the players—to be used as reference points.

Week Two

Doing a rough map of the starting area on hex paper or graph paper begins the visualization process. It’s recommended creators make a key to this map and then plot out about half a dozen major features that players will explore to varying degrees. This is the week that puts down the foundation for all the essential activities that the players will eventually encounter. Where can the players find help? Where is the focal point for adventure? Is there a safe zone they can discover? What obstacles will be in the way? The point is to build up the starting region where players can get a feel for their characters and the game and set up a base of operations before tackling the big task.

Week Three

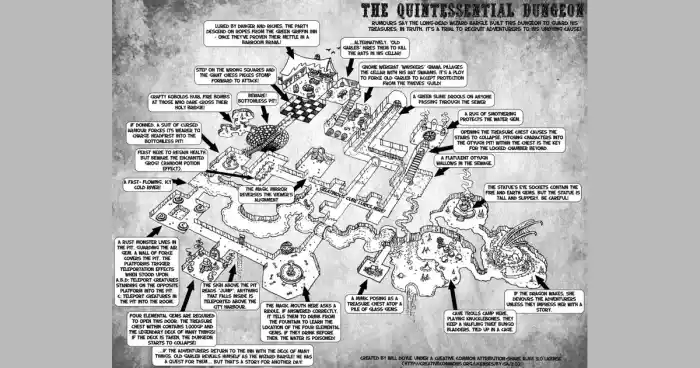

At this time, creators do a rough draft of the main dungeon. Of course, depending on the game, this “dungeon” could be the lair of a dragon filled with treasure, a corporate compound holding industrial secrets waiting to be stolen, or a derelict manor inhabited by vampires addicted to the blood of a semi-petrified Elder God they discovered under the subbasement. In any event, creators give this “dungeon” unique features and different ways up or down to its various levels that contain the areas the players will explore. Creators also populate this dungeon with unique monsters, obstacles, and rewards.

Week Four

Now the creator builds the city or relatively safe zone where the players can rest up, gather intelligence, and have a variety of social encounters. Again, creators are encouraged not to design every detail but enough for the players to feel like they’re in a living place and where they can get invested in other aspects of the setting, like rival factions, and meet the characters that inhabit this space. It’s suggested to come up with a handful of central NPCs (Non-Player Characters) who can influence the players with different needs or agendas that can add depth and texture to the adventure.

Don’t Make More Than You Have To

Week Five

In the final phase, creators sketch out the broad strokes of the wider world into which the players will move as their adventures continue. Where all can the players eventually go? Who is in charge in wider scope? Who are the allies or antagonists the players might likely encounter? What are the rumors out there to follow for more adventure, fortune, and glory? The idea here is to keep unfolding the textures and wonders of the setting so everyone can have fun playing the game and having unique adventures.

Challenge Accepted

In the document, Otus also provides a sample that can be followed step-by-step that works as a touchstone while creators are working their way through the material. This way, if a bullet point seems vague or the language makes it unclear, a model is laid out in parallel as an easy guidepost.

On the whole, “The Gygax 75 Challenge” is an excellent design tool that can be helpful for new and experienced designers for any TTRPG. Additionally, Otus provides the document for which anyone can name his or her own price to download it, so the barrier for entry is negligible. There’s almost no reason to not give this a try for anyone interested in running a TTRPG.

Click here for the Gygax Challenge.

© 2023 Seth Tomko