Rage, oh Muse, Sing of Rage

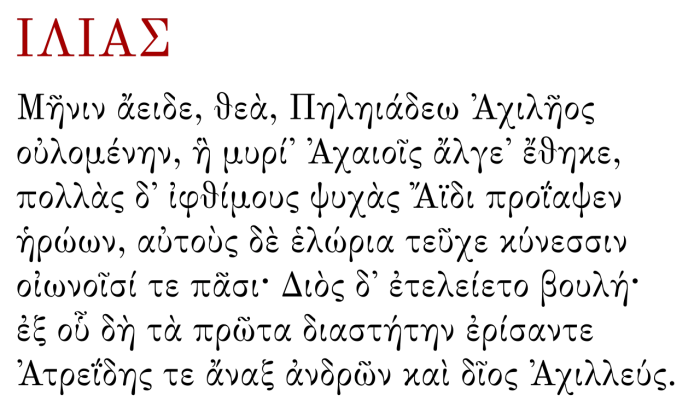

Not content with available translations of Iliad, Alessandro Baricco set out to fashion the text to be readable for the current era, even by people not familiar with Homer's epic. In his notes to the text, the author explains he found no suitable versions of Iliad to use for a public reading as was historically often done. Using Homer’s epic, he refashioned the text to appeal to modern readership and revive public interest in the ancient Greek poem. This undertaking was important to Baricco because Iliad itself was a work meant to be heard as well as read.

All of the broad strokes and many of the details from the epic are preserved. Virtually nothing of the main war plot and how the human participant gets casually excised in this edition. Likewise, the muscularity of the language is on par with scholarly translation such as that by Robert Fagles. The violence is graphic, the speeches are rhetorically impassioned, and the few moments seen outside of the war are tender. The spirit of the epic is preserved even if every line of poetry is not.

Readers unfamiliar with Homer’s epic or pre-Classical Greece will not feel left out. Though the narrative speeds towards it violent and mournful conclusion there is little jargon or archaic language or customs that are not given at least a passing explanation, such as certain familial relationships or the events leading to the war at Troy’s gates.

Twilight of the Gods

A telling absence in the novel is that of the gods. They make almost no appearances in Baricco’s work, a clear departure from Homer’s original poem. This choice, however, places the war and events in it squarely in the hands of the human participants. To everything that Homer attributes divine guidance, Baricco explains through other phenomena or as resulting from natural sources. The lifting of large boulders, for example, is a matter of perspective or even adrenaline surges from being in combat. Such a perspective is in line with many modern writing styles in which thoughts and actions Classical writers and thinkers would have attributed to external sources (the gods), contemporary writers put in the minds of characters. This of course is a different tactic from an author like Madeline Miller who fully leans in to the magic and supernatural elements in her Classical retellings The Song of Achilles and Circe. Both styles have their place, and the audience must determine for themselves which works best.

New Point of View

Because the gods are out their wider perspective in Homer’s Iliad goes with them. To cover this ground, Baricco uses multiple narrators, sometimes switching between them within a chapter. All such changes are clearly marked, so there is no need to worry about getting lost in the transitions. Chapter headings also make following along no difficult task, and it allows different characters to quickly develop distinct voices.

Where Baricco has significantly altered the text—usually in regards to how certain characters feel about their circumstances—he puts the text in italics. In this way readers see where Homer begins and Baricco’s interpretation takes over from the source material.

Bonus Features

Aside from the exquisite rendition of the epic, the Knopf edition also includes both Baricco’s note on the text and his note on war. The latter is essentially a short essay concerning the author’s feelings toward war and what Iliad says about violent human conflict. It makes a compelling argument about what has and has not changed about war since Homer’s era and why war remains a feature in the world.

An Iliad by Baricco is an excellent book to have as either a companion to Homer’s Iliad or even as a stand-alone interpretation of inherited cultural myths. The brevity and engaging language of the novel make this a first-rate addition to any bookshelf.

Source

Baricco, Alessandro. An Iliad. Trans. Goldstein, Ann. New York: Knopf, 2006.

© 2009 Seth Tomko