The Hero's Journey: Women in Literature

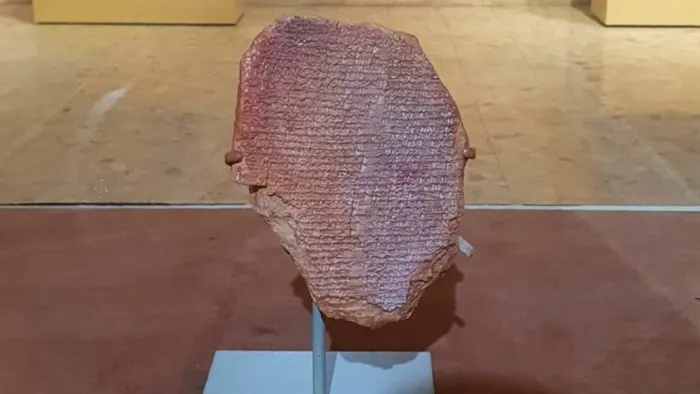

The goal of the mythic journey of the hero is to find wholeness or special knowledge that will restore balance to the hero and the community. Often, this culmination of awareness is held by or embodied in a female character the hero encounters on his quest. However, the female can be dangerous because her knowledge has the potential to create or destroy, depending upon how she is approached and how her power is used. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, women represent not only great wisdom and power but also temptation and ruin.

As understood by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, women play an integral role in the hero’s progress on his journey. A meeting with her often occurs close to, if not at, the apex of the heroic quest. Campbell explains, “Woman, in the picture language of mythology, represents the totality of what can be known. The hero is the one who comes to know” (116). It is a woman who is the greatest aid to the hero since she can provide him with the information he requires to change himself and the world. She becomes a stand-in for the mother-goddess, a symbol of all the splendor and strength of the natural world. As Campbell describes, “She is the incarnation of the promise of perfection” (111). By joining with her, the hero is freed from the illusion of opposites and becomes the lord and knower of his own fate. This union is achieved through a representational marriage with this goddess figure, which is how the hero displays his “mastery over life; for the woman is life, the hero its knower and master” (120). It is through the woman that the hero understands himself and his quest.

At the same time, a woman with all her mystery, knowledge, and power can be threatening and beguiling. Campbell warns, “Fully to behold her would be a terrible accident for any person not spiritually prepared” (115). Just as nature can be dangerous and treacherous to those who travel in the wild without correct preparations, the goddess can be an agent of destruction. Campbell writes that the goddess-figure “is also the death of everything that dies” (114). The hero has to recognize this aspect of the feminine and treat it appropriately by either rejecting her temptations or harnessing the power she represents.

In Gilgamesh, two women convey learning and wisdom. The Priestess Shamhat is the first woman sent to tame the wild man, Enkidu. She does this by going out into the wilderness where she “stripped off her robe and lay there naked [….] For seven days / [Enkidu] stayed erect and made love with her” (79). The sex act leads Enkidu into manhood and signals a break from the uncivilized, animal world he has formerly inhabited.

The beginning of the civilization process continues to involve eating “human food,” hygiene, and civic responsibility (85-6). Of course, before he goes with Shamhat to live with people, Enkidu tries to rejoin the wild animals, “But the gazelles / saw him and scattered” (79). His union with the priestess has brought Enkidu into domesticated life, for Enkidu realizes “that his mind had somehow grown larger, / he knew things now that an animal can’t know” (79). Shamhat, in her role as a stand-in goddess, is a benevolent force that brings knowledge and civilization to a great hero, preparing him for the trials ahead.

The second prominent woman in Gilgamesh is the tavern-keeper, Shiduri. Gilgamesh meets her while he is wandering after Enkidu’s death, looking for a means of immortality. When the King of Uruk explains himself and the nature of his journey, Shiduri questions his judgment and explains what seems best to her.

Humans are born, they love, then they die,

This is the order that at gods have decreed.

But until the ends comes, enjoy your life,

Spend it in happiness, not despair [...]

That is the best way for a man to live. (168-9)

She encourages him to put away his grief and enjoy everything he has in his life. Otherwise, he is just trying to run away from death. Though Gilgamesh does not heed her at the time, Shiduri offers him a treasure of practical wisdom in the way Campbell describes a woman who symbolizes the goddess. Of course, by rejecting her knowledge and her help, Gilgamesh suffers greatly and even fails in his attempt to make himself immortal.

The other goddess incarnation is that as a destroyer. In this aspect, she can be enticing or fearsome or appear however she desires to tempt and test the hero. Because the goddess represents everything in the world, she must also be seen as dangerous and negative. Campbell explains that the goddess figure “is the womb and the tomb: the sow that eats her farrow. Thus, she unites the ‘good’ and the ‘bad,’ exhibiting the remembered mother, not as personal only, but as universal” (114). If the hero comes to understand her and himself, he proves his spiritual growth and his worthiness in inheriting her power.

In Gilgamesh, this destroyer-goddess can be seen in the goddess Ishtar. When she sees Gilgamesh return victorious over Humbaba, she descends to Uruk and addresses the king. She says, “Marry me, give me your luscious fruits, / be my husband, be my sweet man. / I will give you abundance beyond your dreams” (130-1). Ishtar offers to make Gilgamesh wealthy, his kingdom fertile, and respected by all people in the world. All he will have to do is agree to be Ishtar’s husband.

However, Gilgamesh does not fall into her snare. He replies, “Your price is too high, / such riches are far beyond my means. / Tell me, how could I ever repay you [….] And what would happen to me / when your heart turns elsewhere and your lust burns out?” (132). His answer shows that Gilgamesh is aware of his limitations and mindful of Ishtar’s nature. He recites a list of Ishtar’s former lovers and the wretched ends they met when they inevitably failed to please the goddess. Concluding his argument, Gilgamesh says, “And why would my fate be any different? / If I too became your lover, you would treat me / as cruelly as you treated them” (135). With this solid sense of self, the King of Uruk spurns Ishtar and the future she offers because he knows whatever delights she provides will be short-lived, but her unavoidable wrath will be catastrophic. Coming into this knowledge gives the reader a hint of the great king Gilgamesh can become as long as he stays focused. The encounter with Ishtar proves he can be a clever hero since the offer of an easy life does not seduce him.

As understood by Campbell, various aspects of the goddess figure are present at different times and in different characters in the texts. The creative and beneficial features of the cosmic feminine principle are evident in the priestess Shamhat and tavern keeper Shiduri. The dangerous side of the goddess is represented in the fickle, destructive goddess Ishtar.

Sources

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1949.

Gilgamesh. Trans. Mitchell, Stephen. New York: Free Press, 2004.

© 2011 Seth Tomko